In addition to being a mom and an author, Sarah Chorn is also an editor, a photographer, and a gardener. On top of that, today happens to be her birthday! Her second novel, Of Honey and Wildfires, was just released this week. Here, Sarah writes about the history of child labor in the mining industry in the mid-1800’s, and how her research influenced elements of her new book. Thanks for this, Sarah! The first-ever guest post for the blog!

The magic system (called “shine”) in Of Honey and Wildfires is based on oil and coal, specifically in the mid-1800s. I like to base most of my world building on real-world events, twisting them enough to fit the secondary world I’ve created. One of the things I had to decide in this book was how exactly were these people going to get their shine out of the earth. So, I did research, and I learned that there was a large and flourishing child labor system in the mining industry in the mid-1800s, and as soon as I started to learn about it, I knew I had to mention it somewhere in the book.

In Victorian times, it was not unheard of for children to work, starting at very young ages. In fact, it was quite a common practice. With very little in the way of social safety nets, often entire families would rely on everyone in the family working themselves to the bone as soon as they could, just to get food on the table. Just to survive.

Often, children pre-1842 in England, would start working in the mines around the age of eight, though sometimes as young as five years of age. These children would work jobs down in the dark, for as long as the adults, if not longer, and for less pay. Often they’d be down in the mines starting at five or six in the morning, and not get out until six or seven at night.

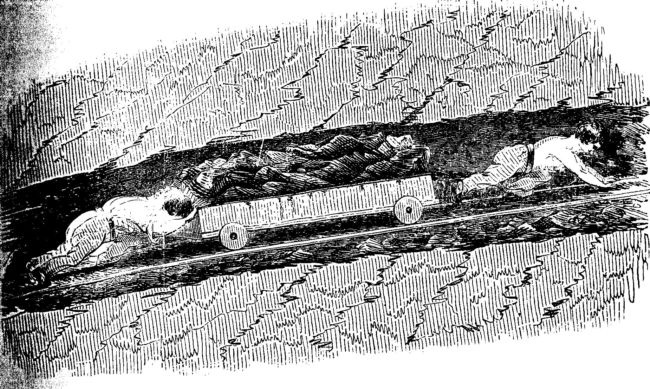

There were a few different jobs that children in the mines would typically work, though most of them involved sitting in the dark for long hours, or chained to carts, or fitting themselves into tight areas that adults couldn’t get to.

Image of children working in a narrow underground railway.

Image of children working in a narrow underground railway.

In 1842 in England, a law was passed that stopped women and children under the age of ten from working in underground mines in England. (Learn more about this, and the typical jobs children worked here)

Often, children would spend hours alone in the dark, or they would be chained to carts. Typically they would have to pay for the oil they used in the lamps they brought down with them and the such. Furthermore, mines were not safe at this time. With an eye toward profit more than safety, there were often accidents down there in the dark, often by flooding, or a tunnel collapsing, or an explosion, as described here:

“Nearly a year ago there was an accident and most of us were burned. I was carried home by a man. It hurt very much because the skin was burnt off my face. I couldn’t work for six months.”

Phillip Phillips, aged 9, Plymouth Mines, Merthyr

(Read more here)

Furthermore, poverty often meant that many parents would know of accidents, poor conditions, or even abuses their children were suffering, but were unable to do anything about it. Everyone needs to eat, and often chances were limited as to how to get the food a family would need to survive. It wasn’t unusual that children actually preferred to live at work, no matter how rough the conditions, because the conditions at home were even more cramped and squalid. (more here)

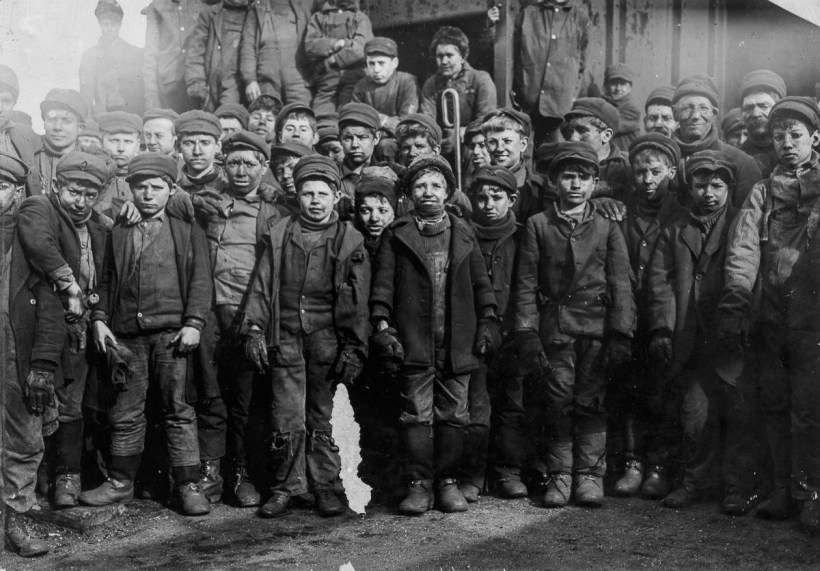

However, this was not something that was just relegated to the UK at the time. Over here in America, we had a booming child labor industry, especially with mining. In 1910, it was assumed that some 2 million children in America were employed in the mining industry. In 1904, the National Child Labor committee was formed. They then hired Lewis Hine, a photographer and sociologist, to travel around the country and document the conditions children worked. Mashable put together a bunch of these photos on this website (which you really need to take a look at). They were part of what was used in the effort to pass the Keatings-Owen Child Labor Act in 1916.

Breaker Boys, employed by the Pennsylvania Coal company, 1911. Photo by Lewis Hine.

Breaker Boys, employed by the Pennsylvania Coal company, 1911. Photo by Lewis Hine.

Taking into consideration the necessity of children needing to work, and a poor social safety net to protect them, one can assume a lot of things about the industry as a whole. For example, at such a young age, many children suffered prolonged health consequences due to their work. Mining, for example, left many children with terrible eyesight due to spending their entire days down in the dark starting at such a young age. Inhaling coal smoke gave a lot of them permanent respiratory illnesses with often fatal results. Furthermore, injures were common, and infection due to injuries could almost be guaranteed.

Also, considering the fact that these children were often times working in the dark, around adults, and a lot of times they would have torn or ill-fitting clothes. Crimes and abuses happened, and when they happened in the dark, with no witnesses, or no witnesses willing to come forward, what could a child really do? Furthermore, taking into consideration that often their next meal relied on them making some kind of income, there as often little incentive to speak of such incidents. It paints a rather terrible, tragic picture, doesn’t it?

Child labor does not fill a lot of Of Honey and Wildfires, but it does play a role in part of the book, as well as a conversation that happens wherein someone who was a child working in the mines, hacking shine out of the earth, tells his story about being a child laborer. A lot of what he says is based on what I have written here. He had to pay for the tools he used. He saw crimes committed, alludes to the fact that he may have been assaulted as a child. He talks about kids being chained to carts so they could pull them through the mineshaft, and he talks about a time when someone got burned, and he had to carry the boy out of the mine so he could be healed, which was based on that eye-witness story I listed above.

Perhaps what bothers me the most about learning all of this is that it did not end. Not really. Not with laws. There is still child labor happening all over the world. One of the best books I read last year, in fact, is called The Outlaw Ocean, and in part of that book, he discusses children who are basically slaves to these fishing boats. Due to international laws, huge swaths of the oceans are largely unregulated, and so these companies get away with it.

There is also plenty of cases of children working in diamond mines and as indentured slaves, sexual servitude and so much more.

While I based my child labor in Of Honey and Wildfires on Victorian and US child labor in the mining industries in the mid 1800’s to early 1900’s, I fell down a deep and terrible rabbit hole where I learned about all sorts of forms of it still going on today. It is a horrifying fact that child labor has always existed, and likely always will, though we can do our part to help educate and work against it.

My goal in Of Honey and Wildfires was to base the stories being told about child labor on as much fact as I could, while not hiding or glorifying any of the ugly details. I wanted to perhaps touch on the emotional impact of those who had lived it, as well as the one person who was facing these hard, ugly truths for the first time. I wanted to show that these things happened, and it’s important to know that, but we also have the power to change things for the better. Even now.

All those kids trapped down in the dark.

He wondered if the earth felt pain.

He wondered if he was standing on the buried screams of forgotten children.

— Of Honey and Wildfires

Catch up with Sarah on her blog or on Twitter, and click on the cover images to purchase her books!

One thought on “Guest Post: Sarah Chorn”